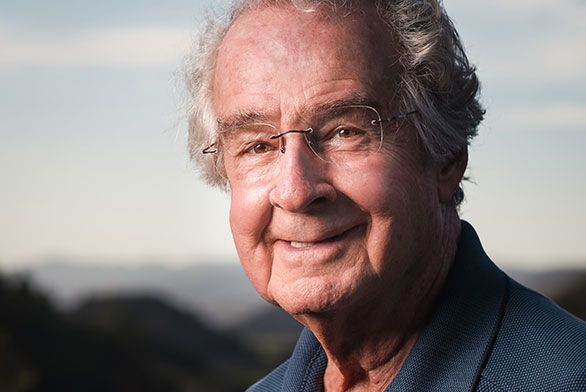

Lifelong Steward of the Program: Warren Winiarski's Enduring Legacy

June 20, 2024 | By Kerri Braly

The pioneering winemaker forged a future for American vintners—and his generosity secured the future for St. John’s College.

Those who knew Warren Winiarski (Class of 1952) as a pioneering winemaker could tell that he viewed a good wine grape with a kind of reverence, recognizing and admiring all the complex elements that were held in harmony. This small fruit could produce something marvelous.

Those who knew Winiarski as a philanthropist and as a philosopher, teacher, and mentor often saw him in much the same way.

“He was just an incredible person to know,” says Zach Rasmuson (A95), a member of the Board of Visitors and Governors whose own winemaking career was inspired by Winiarski. “He was at various points in my life an employer, a teacher, sometimes my critic, but more often my friend.”

On Friday, June 7, 2024, Winiarski, a beloved alumnus and an extraordinarily generous donor, passed away at the age of 95. He and his wife Barbara (Class of 1955), who died in 2021, were deeply involved in the St. John’s community for more than seven decades, offering transformative financial support while actively contributing to the ongoing intellectual life of the college.

The couple’s philanthropic investment in St. John’s currently stands at more than $65 million and will increase substantially as the final bequest is realized. Their most significant gift, a $50 million challenge match that helped catalyze the successful Freeing Minds campaign, remains the largest individual gift ever received by the college.

“No one was more committed to St. John’s and our academic Program. No one. He loved it, and he believed it its transformational power,” says President Mark Roosevelt.

Winiarski’s commitment to the college includes 23 years on the board, where he helped steer St. John’s through a period of change that included the Great Recession. In 2010, Winiarski was named a trustee emeritus in recognition of his longstanding and meritorious service. He also spent 26 years teaching weeklong seminars at the Summer Classics Program in Santa Fe, making him one of the first non-tutors to do so.

Although his impact on St. John’s and the California wine industry was immense, Winiarski took an indirect route to both. Born in 1928 in a working-class Chicago neighborhood, he grew up watching his father make wine and mead as a hobby using honey, fruit, and dandelions. At the time, the young Winiarski didn’t see winemaking in his own future; later in life, he recalled how he would press his ear to the bubbling barrels, intrigued by the alchemy of fermentation.

An ardent conservationist, Winiarski was awed by the forces he saw at work in water, air, and soil. He initially studied forestry at Colorado A&M but found the curriculum too technical, with little opportunity to explore fundamental questions of “how” and “why.” Mortimer J. Adler’s How to Read a Book introduced him to the Socratic seminars and Great Books curriculum at St. John’s, prompting Winiarski to transfer to Annapolis. “It talked a lot about St. John’s, and I realized that’s where I need to be,” he said of Adler’s 1940 bestseller.

Winiarski would describe his time at the college as “paradise.”

It was at St. John’s that Winiarski met his future wife, Barbara Dvorak. A gifted painter and a trailblazing intellectual in her own right, Barbara was among the first women to graduate from St. John’s. The couple married in 1958 and had three children: Kasia (A84), Stephen, and Julia (SF92).

After St. John’s, Winiarski embarked on a career in academia, pursuing a doctorate in political science at the University of Chicago. His studies took him to Italy, where he spent a year conducting research on Machiavelli—and falling in love with Italians’ appreciation for the everyday pleasures of good food and fine wine. Returning to Chicago, he taught in the Basic Program of the University College, itself modeled on a Great Books curriculum, but the call he had heard long ago from those bubbling barrels grew closer. He pored over texts on the art and science of winemaking, once even attempting to make wine in his campus apartment. “He just stepped confidently into the unknown,” says friend and fellow Visitor Emeritus Steve Feinberg (H96). “And he always credited St. John’s with his ability to do that.”

In 1964 the family headed west to California’s Napa Valley, drawn to what Winiarski and Barbara described as a “simpler lifestyle” in the heart of California’s wine country. There he apprenticed with local vintners, including Robert Mondavi Winery, until his discovery of a small prune orchard along a rocky promontory in the Stags Leap Palisades changed history. The Winiarskis converted the property into a vineyard they christened Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, and a few years later this unique terroir of volcanic soil and cool ocean breezes would catapult Winiarski to international prominence. In a blind tasting at the 1976 “Judgment of Paris,” his 1973 SLV Cabernet Sauvignon triumphed over the finest French Bordeaux, a stunning upset that forever changed the global perception of California wines. A bottle of the wine now resides in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection at the National Museum of American History.

“He was a remarkable man, and you could tell he was a Johnnie because he was such a passionate seeker of knowledge,” Feinberg says. “That’s what made him a great vintner.”

The passion that led Winiarski to success as a winemaker had its parallel in his dedication to education, especially to the liberal arts as practiced at St. John’s. Throughout his life, Winiarski made the college a priority for his philanthropy as well as his time. “Warren was the most serious board member I ever knew,” says Feinberg, whose own service to the board coincided with that of Winiarski. “I am convinced there were times when he saved us from making poor decisions. That’s because he was willing to question everything, relentlessly, with the goal of preserving this education.”

Winiarski also understood that achieving such a goal entailed personal sacrifice, current board chair Warren Spector (A81) adds. “He was on the board for two important fundraising campaigns, and for discussions around a third. He gave generously, at increasing levels, to each of them.”

The Winiarskis’ generosity touched all aspects of life at St. John’s, from strengthening the financial stability of the college to providing regular annual support for essential needs. The couple also contributed to infrastructure projects on both campuses, including the creation of the Winiarski Conversation Room in Annapolis and the construction of the Winiarski Student Center in Santa Fe. The latter, funded by a $7.8 million contribution to the college’s With a Clear and Single Purpose campaign between 2002-2008, was particularly close to their hearts, as it enhanced student life on the campus where their daughters had both studied.

In 2018, the Winiarskis made their most transformational gift: the $50 million Winiarski Family Foundation Challenge. Launched as part of the Freeing Minds campaign, the challenge matched every campaign gift with an equal contribution to the St. John’s Endowment. Inspired by the opportunity to double their impact, alumni and friends responded with more than 17,000 individual gifts, meeting the challenge in spring 2021.

“Our parents were transformed by their time at St. John’s, and their love for college and the Program never wavered,” daughters Kasia and Julia told St. John’s College. “Through all their years working together in business, raising a family, and in their own pursuits, the gifts of the Program were with them as guiding spirits. It was their abiding wish that class after class of students would have the same opportunity that they so treasured and which can be found nowhere else.”

Two years later, the Freeing Minds campaign closed with $326 million raised toward a $300 million goal. “The success of Freeing Minds is going to accomplish exactly what Warren and Barbara hoped it would. It will ensure our financial stability so we can continue to offer this education and never have to compromise on who we are,” says Annapolis President Nora Demleitner.

Generous as he was, Winiarski did not let his role as benefactor overshadow that of thinker. He was a regular participant in Santa Fe’s Summer Classics Program, where he co-led seminars on the works of Shakespeare, Aristotle, and of course, Machiavelli. “There was something very natural about his return to campus each summer,” says Santa Fe tutor Judith Adam, who taught alongside Winiarski for 18 of his 26 seminars. “He was a man who loved to read, loved to think. He was on a path to being an academic when life led him in another wonderful direction. Being involved in Summer Classics was his coming home.”

Those who were close to Winiarski say he brought the thinker’s perspective—the ability to listen and reflect—to his whole life, including his time as a vintner. Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, which Winiarski owned until its sale in 2007, even had its own Foucault pendulum.

“He always wanted to know where the earliest wine came from, since it’s mentioned so often in the classics. Many years ago, he brought back cuttings from Pakistan so he could make wine from what he believed to be the original vinifera,” Feinberg recalls. “I asked him once, ‘How was the wine?’ He said, ‘It was terrible.’”

“It was just this tiny thimbleful of wine, but we drank it together, and it was the culmination of a life’s worth of curiosity,” recalls Rasmuson, who is now the executive vice president of The Duckhorn Portfolio and one of at least 15 Johnnie winemakers active in the industry. “He showed me that a purposeful life could still be a reflective life.”

In recent years, Rasmuson and other Johnnie winemakers have, like Warren, returned home to the Santa Fe campus during Summer Classics to participate in seminars and other events as part of Johnnie Winemakers Weekend.

“A few summers ago, I had the privilege of honoring Warren by leading a seminar on a piece of text he had written. There is a passage that reads: ‘To truly understand something, you must get to know it at its best. For when something is at its best, it is mostly truly itself,’” Rasmuson says.

“Warren wanted nothing more than for St. John’s to remain true to itself—and after all that he and Barbara have done for the college, there are a lot of people, including me, who are far more confident that it always will.”

In 2023 Winiarski made his final gift to the college, a verbal commitment to name St. John’s as the remainder beneficiary of his estate. His final request: that the college always remain true to its core.

“The goal of his extraordinary philanthropy was to maintain this education for generations to come. In that regard he could be tough. He did not accept vagueness or glibness. But it was always clear that his overriding objective was to help the college that he loved,” Roosevelt says. “Tutor Eve Brann has said that we should all seek to find someplace we love and make it better. Warren Winiarski was the embodiment of that advice, and we all owe him a tremendous debt of gratitude.”

Alumni and friends who wish to offer their condolences are encouraged to reach out to the Winiarski family at the following email: